Long Pregnancy Series: Consent

Posted on

At this point in the series it is important to discuss what consent is, and critically, what it is not. This section carries a * SENSITIVE CONTENT WARNING * because some of the things discussed here can be upsetting if you have experienced them or something like them.

Anything less than a “hell yes!” is a no

Consent must be gained for medical procedures. It is required by law, and it is an ethical and moral obligation in regards to respecting a patient’s autonomy. The BMA defines consent as valid if it meets the following conditions:

- The individual giving consent has to have the mental capacity to be able to make the decision in question.

- Consent has to be given voluntarily – consent where an individual has been coerced into making the decision will not be valid.

- Sufficient information also has to be offered to enable the individual to understand the nature of the decision and its likely consequences, including the consequences of declining the treatment or intervention.

Another useful tool you can use is the acronym FRIES. Consent that is valid is:

Freely given, meaning no coercion or persuasion

Reversable, meaning it can be withdrawn at any time

Informed, meaning all the benefits and risks of all of the available options have been discussed

Enthusiastic, meaning it is not reluctant or resigned

Specific, meaning it only applies to the one thing being discussed, and not to anything else

If it is not all of those things, the individual has not given valid consent.

Informed refusal

Inherent in informed consent is the right to informed refusal. If someone has been given the opportunity to give valid consent it naturally follows that they may refuse consent for any treatments entirely. Informed refusal is just as important as informed consent.

Saying no while pregnant

I will preface this section with an acknowledgement that there are midwives and obstetricians out there who are wonderful. They listen to their patients and do their utmost to work with their wishes, and they gain consent properly before carrying out procedures. That being said, it is important that we have open and honest discussions about those occasions where that doesn’t happen, those people who don’t get proper consent, who bully, threaten, withhold information and do procedures without asking. The only way this reality can change is by recognising it and calling it out.

NICE states: “If a woman chooses not to have induction of labour, her decision should be respected. Healthcare professionals should discuss the woman's care with her from then on.”

Slightly facetious side point: Surely healthcare professionals should

have been discussing her care with her for her entire pregnancy??

Why would that only start after 42 weeks?

Despite the fact that coercion is not valid consent, and that informed refusal is recognised by the NHS as something that must be respected, the reality is that often the decision to decline a standard antenatal or intrapartum care pathway is met with irritation, exasperation, anger, threats, shroud waving, and/or intimidation. Start a conversation with a group of doulas about a client saying no and it is only a matter of minutes before someone recounts a story of somebody “pulling the Dead Baby Card”. The fact that that particular tactic has a name and that everyone in the room (and probably also everyone reading this) knows exactly what it means is, frankly, a damning indictment of our maternity services.

Pro tip: It’s also coercion.

When is consent not consent

Here are a couple of examples, each of which illustrates at least one way in which consent was not properly sought.

A mother of three, describing her experiences with her first two long pregnancies:

"I was pressured into monitoring; I reluctantly agreed. Then after everything was fine I wasn't allowed to leave until the consultant spoke to me and warned me again of the risks. I heard them and wanted to leave. As I still wanted to go home and not have an induction (purely based on going over dates) he got another two male consultants to speak to me. I felt pressured and overwhelmed. After days of this I finally agreed to (was pressured into) induction. I was emotionally exhausted. I was so fearful he would die as I was told this was a possibility (again, no issue other than post dates). The induction failed and I had an emergency csection due to distress.

In my second pregnancy, they were constantly reminding me that my placenta could fail at any moment and it was a risk I was taking going past dates and not having an induction. Reminding me that, despite me making clear I wouldn't accept an induction unless it was a life vs death situation, they still wanted to book me in anyway. It placed huge pressure on me. I made it clear it triggered my PTSD. They weren't fussed about that."

Allow me to list all the ways the consent given here is not valid:

- she reluctantly agreed to monitoring, after being pressured

- she felt pressured and overwhelmed because she was deliberately ganged up on and intimidated by 3 male consultants

- she was pressured for days until she gave in

- she was afraid to say no to the induction because she was repeatedly being told her baby might die

- she gave her answer but they kept talking about induction anyway (in both pregnancies)

Here is another mother, speaking about the end of her second pregnancy:

“I was told they would do a sweep when I was 40+5 (it was Xmas so would have been sooner had they been open!) to try and avoid induction."

This is not consent. Consent would be: saying that a sweep could be done, here are the benefits and the risks, and giving an appropriate amount of time to consider what has been discussed before asking for a decision. Consent asks, it does not tell.

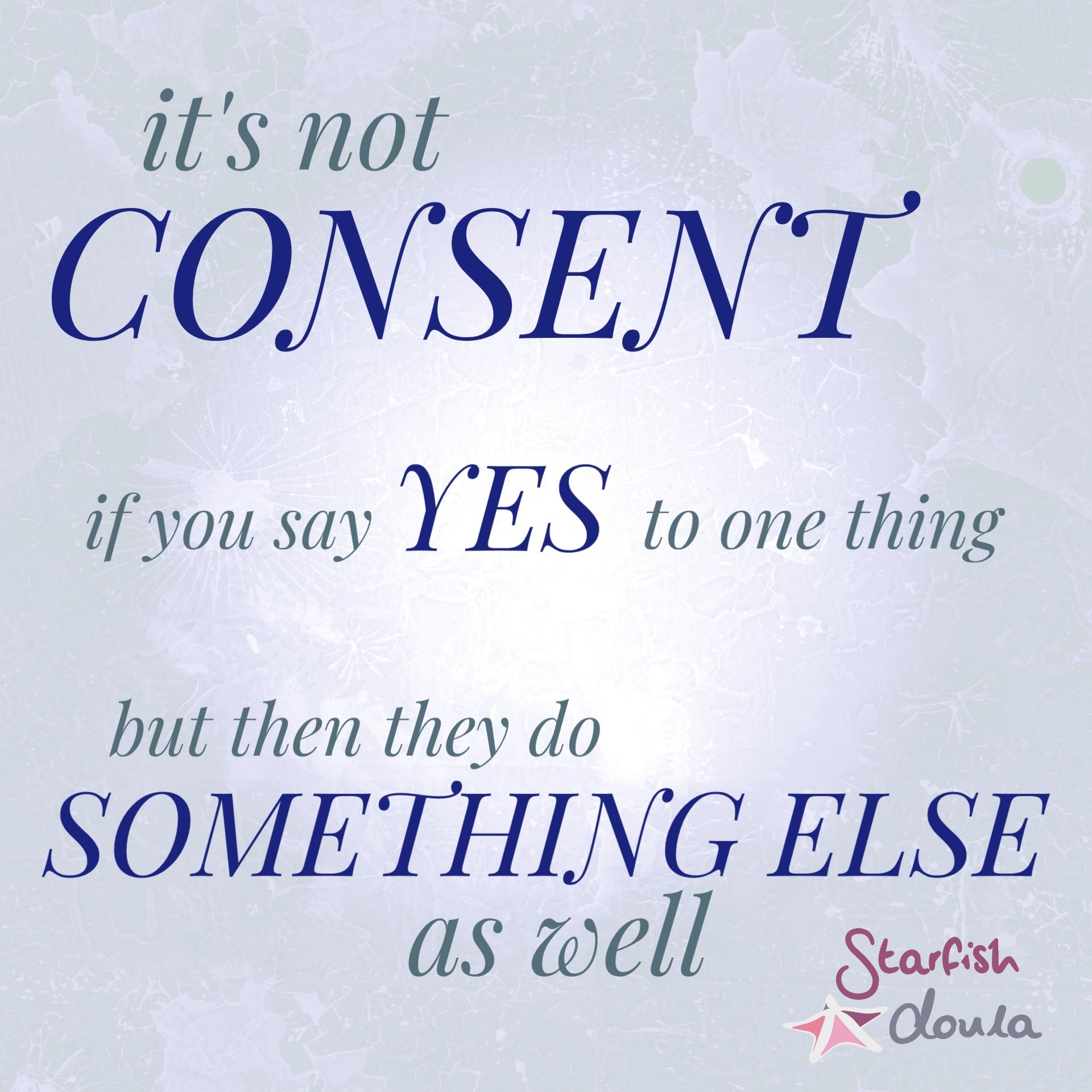

Here are some images which may help to define when consent is true consent, and when it is not:

Why does this happen?

This isn’t a short answer.

I would love to say that the issues with consent outlined above have come about in the past few years since Montgomery vs Lanarkshire (2015). This was an important case which redefined how consent may be conceptualised and navigated. In the case ruling, it was determined that an individual cannot consent to medical treatment if the risks of the treatment have not been given, and that the patient must be given any information they want to have, not just the information the doctor thinks they should have.

“The ethical and legal position is clear:

doctors must not withhold information simply because

they disagree with the decision the patient is likely to make

if given that information.” - BMJ, 2017

It would be reasonable to assume then, that since this ruling, health care professionals have had to become a lot clearer about the risks of choosing a particular pathway, or they risk bringing themselves under investigation for medical assault of a patient who hasn’t properly consented. It would be reasonable to think that now they are simply (very heavily) outlining risks that were previously not talked about, because if they don’t they may sued for negligence and/or assault. I would love to say that this is something that has only been happening in the last few years as an unfortunate side effect of the case ruling.

I would be lying.

The aggressive attitude that some people meet when declining medical treatment has certainly been going on for as long as I’ve been supporting women; I began peer-supporting women in 2007, and doulaing professionally in 2012. I have no doubt it was going on for decades before I became aware of it. This is not a scenario that has come about because of a recent ruling.

Also, if it were merely that health care professionals now have to be very clear about the risks of any care decisions made, then one would expect that induction is now being presented with an honest disclosure of all the risks involved. This is also not entirely true. Induction is not often presented in an unbiased way; usually it is presented as a wonderful risk free option for “getting that baby out”, or the risks are tacked on to the end of a discussion as though they are some kind of postscript, and it doesn’t matter if you accidentally don’t read them.

A more likely answer is that it happens because of two things: a lack of knowledge about what constitutes real consent, and medical paternalism. Medical paternalism is the attitude (and subsequent practice) of the physician deciding what is in the best interests of the patient, even if those interests go against the patient’s wishes. It is tricky to tease out all of the threads around medical paternalism, not least because there is a significant portion of the population who expect and encourage this attitude. Whether it is because they doubt their own ability to make those decisions, or because they don’t want the responsibility if something goes wrong, it is incredibly common to hear statements along the lines of “I know the doctors know best...” or “when I had my babies we just did what we were told”.

Attitudes like that are hard to shake. Montgomery is actually beneficial because it is acting to challenge medical paternalism by emphasising the legal stance on consent, and brought it in line with best practice as outlined by regulatory bodies such as the GMC. It is interesting to note that doctors should have already been acting in this way; giving their patients information and supporting them in their decisions.

I remain hopeful that the case reflects a slow shift towards a more cooperative air between consultants, midwives, and those they serve, and that these changes will continue.

Add a comment: